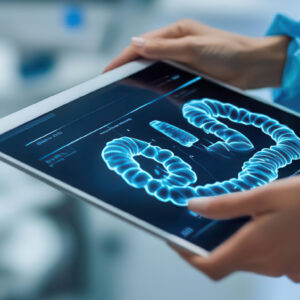

Juvenile polyposis syndrome (JPS) is a rare (incidence 1:16,000 – 1:100,000), autosomal dominantly inherited disease of the gastrointestinal tract (GI) characterized by the occurrence of juvenile (hamartomatous) polyps (from >5 in the colorectal region up to multiple polyps in the entire GI tract). 75% of patients have a positive family history. Clinically, JPS is considered certain if one of the following criteria is met:

- patient with numerous (>5) juvenile polyps in colon/rectum, and/or

- patient with juvenile polyps in colon/rectum and positive family history, and/or

- patient with juvenile polyps in the entire GI tract (stomach, small intestine).

Although most juvenile polyps are benign, 10-50% of patients develop malignant tumors in the GI tract (mainly stomach, colon, pancreas). An early diagnosis is important as the increased risk of tumors already exists in childhood and adolescence, and regular endoscopic controls should be performed.

The molecular cause is a pathogenic variant in the SMAD4 gene or the BMPR1A gene in about 60% of patients. SMAD4 (also known as MADH4, DPC4) is a tumor suppressor gene. The gene product plays an important role in transforming growth factor ß-signal transduction. The BMPR1A (bone morphogenetic protein receptor 1A) gene encodes a type I serine threonine kinase receptor of the TGFß super family. BMP signal transduction is mediated by SMAD4 from the surface receptor BMPR1A. A genotype-phenotype correlation between pathogenic SMAD4 or BMPR1A variants and the clinical symptoms is only possible to a very limited extent. The proportion of deletions of larger gene segments in both genes is up to 15%. In individual cases, pathogenic variants in the PTEN gene (PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome) can be detected in patients with JPS-like symptoms.

References

Cohen et al. 2019, J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 68:453 / Valle et al. 2019, J Pathol247(5):574 / Cichy et al. 2014, ArchMedSci 10:560 / Jelsing et al. 2014, Orphanet Journal of Rare Disease 9:101 / Yang et al. 2010, Dig Dis Sci 55:3458 / Calva-Cerqueira et al. 2009, Clin Genet 75:79 / van Hatten et al. 2008, Gut 57:623 / Aretz et al. 2007, J Med Genet 44:702 / Pyatt et al. 2006, J Mol Diagn 8:84 / Howe et al. 2004, J Med Genet 41:484 / Friedl et al. 2002, Hum Genet 111:108 / Sayed et al. 2002, Ann Surg Oncol 9:901

HEREDITARY DIFFUSE GASTRIC CANCER

Every year in Germany about 6,300 women and 9,300 men are diagnosed with stomach cancer. Approximately 1-3% of all gastric cancers are hereditary diffuse gastric cancer (HDGC). In HDGC patients, familial clustering of the disease and a remarkably young age at disease onset (on average 38 years) are seen. A carcinoma with signet ring cells or of the diffuse type is seen by histopathology.

HDGC is caused by loss-of-function mutations in the CDH1 gene. CDH1 is located on chromosome 16q22.1 and consists of 16 exons. The gene encodes the protein E-cadherin (epithelial cadherin), which is mainly found in epithelium where it is involved in the formation of cell-cell contacts. Furthermore, it plays a role in intracellular signal transduction and embryonic morphogenesis.

In up to 40% of patients with HDGC, pathogenic variants in the CDH1 gene are the cause. Carriers of pathogenic CDH1 variants have a 40-70% (men) and 60‑80% (women) risk of developing stomach cancer in their lifetime. Women also have a 40‑50% risk of developing lobular breast cancer. Furthermore, there is a correlation between the detection of CDH1 variants and the occurrence of cleft lip/palate. Pathogenic variants in the CTNNA1 gene have been detected in a few families that have previously tested negative for CDH1. Apart from CDH1 and CTNNA1, no other genes are currently associated with the occurrence of HDGC. Stomach carcinomas can also occur more frequently in HNPCC syndrome, Peutz-Jegher syndrome or FAP syndrome.

According to the current S3 guideline for gastric cancer, the following criteria are indicative of hereditary diffuse gastric carcinoma:

- two or more first and second degree relatives with gastric cancer (regardless of age), one of whom who has diffuse gastric cancer; or

- a family member below the age of 40 who has diffuse stomach cancer; or

- one family member who has diffuse stomach cancer and another family member with lobular breast cancer, one of whom was diagnosed before the age of 50.

Furthermore, testing should be considered for the following families:

- two family members with lobular breast cancer before the age of 50, or one person with bilateral lobular breast cancer also before the age of 50; or

- detection of a diffuse gastric carcinoma and cleft lip/palate in the family; or

- histologically verified in situ signet ring cell carcinoma and/or pagetoid spread of signet ring cells.

Regular endoscopy or chromoendoscopy examinations are recommended for clinically proven HDGC. If a pathogenic CDH1 variant is detected, a prophylactic gastrectomy is indicated. Women with a CDH1 germline variant should undergo more intensive breast examinations from the age of 30. Blood relatives and offspring of CDH1 carriers can be specifically tested for the variants detected in the family after genetic counselling.

References

Leitlinienprogramm Onkologie: S3-Leitlinie Magenkarzinom, Langversion 2.01 (Konsultationsfassung), 2019 / Figueiredo et al. 2019, J Med Genet 56:199 / Kaurah et al 2018, Hereditary Diffuse Gastric Cancer, GeneReviews®, www.ncbi.nlm.nih. gov/books/NBK1139/ / Bericht zum Krebsgeschehen in Deutschland 2016, www.krebsdaten.de/krebsbericht / van der Post RS et al. 2015, Gastroenterology 149:897 / van der Post RS et al. 2015, J Med Genet 52:361

*CNV analysis only