Edwards Syndrome, also known as Trisomy 18, is a rare autosomal chromosome aneuploidy in which there are three copies of chromosome 18. In 80% of cases, a complete trisomy 18 is found, in 10% a mosaic trisomy, and in another 10% there is an unbalanced translocation.

Also called

Edwards Syndrome is also known as:

- Trisomy 18

- Complete trisomy 18 syndrome

- Trisomy E syndrome (formerly)

Symptoms

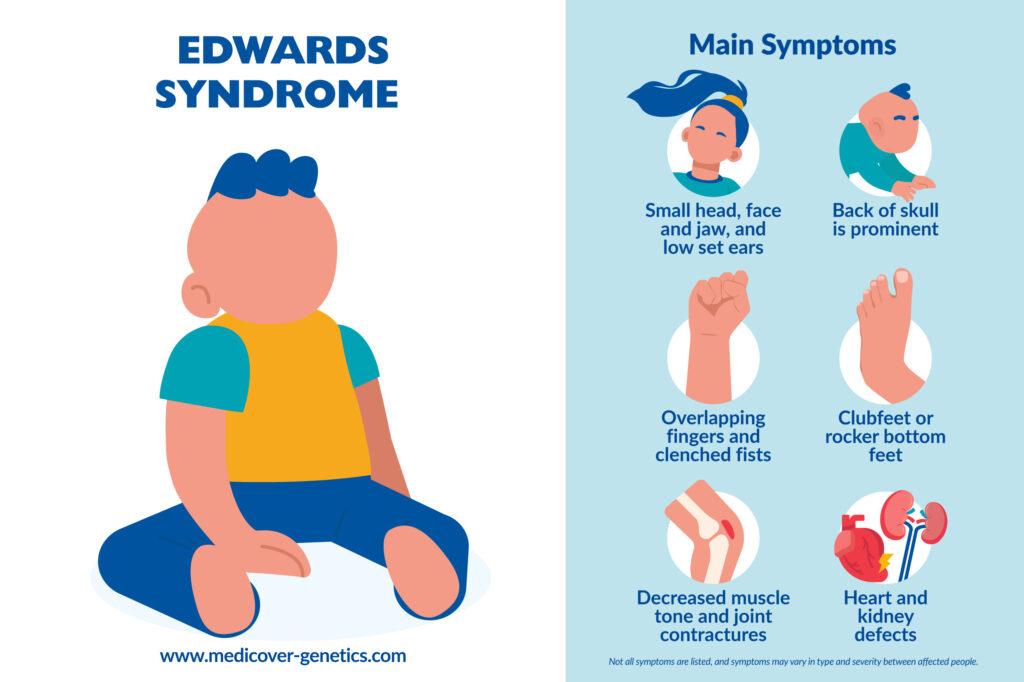

Trisomy 18 is characterized by major and minor abnormalities, affecting all organs and systems. 90% of patients have heart defects, bone abnormalities, and kidney, respiratory, and intestinal problems, resulting in feeding difficulties.

External symptoms are variable; they include:

- Microcephaly (small head)

- Dolichocephaly (head that is longer than it is wide) with prominent back of skull, and a small face

- Microretrognathia (small jaw)

- Low set ears and ear dysplasia

- Prominent calcaneus (heel)

- Rocker bottom feet

- Clenched fists: overlapping of the 3rd and 4th fingers by the 2nd and 5th fingers is characteristic, especially in newborns

- Failure to thrive seen from the prenatal period, as affected fetuses are smaller than average

- Heart defects

- Horseshoe kidney

- Muscle hypertonia

- Joint contractures

- Delayed psychomotor development

Mortality usually occurs within the first few months of life, with over 90% of affected individuals dying within the first year of life.

Frequency

The frequency of Trisomy 18 is estimated to be 1 in 3,000 in live-born infants. Although the prevalence is greater (around 1 in 2,500), the number of fetuses lost during pregnancy and selective terminations after diagnosis due to the severity of the condition is high. 75% of cases affect females.

Causes

Most cases of Trisomy 18 are caused by an extra copy of chromosome 18 in all cells of the body. 5% of the cases have an extra copy of chromosome 18 in some cells of the body, which is known as mosaic trisomy 18. There are also some cases in which a part of the long arm of chromosome 18 is duplicated, which arises mostly from a parental translocation.

Mosaic and partial forms of trisomy 18 are the ones with the best chances of survival; a small percentage that may survive well into adulthood, although with significant developmental and physiological delays. Interestingly, girls with trisomy 18 are found to respond better to treatment and survive longer than boys with trisomy 18.

Maternal age plays a role in trisomy 18, and with the mean maternal age having increased during the last 20 years, prevalence rates of trisomy 18 have risen.

Inheritance

Trisomy 18 and mosaic Trisomy 18 usually occur due to a spontaneous (de novo) error in cell division during the formation of eggs and sperm. Partial Trisomy 18 can be inherited when people carry a balanced translocation of chromosome 18 and another chromosome.

Differential diagnosis

Syndromes with similar symptoms to Trisomy 18 are Patau syndrome (Trisomy 13), and mosaic Trisomy 9.

Treatment

Treatment for Trisomy 18 is tailored to the individual’s specific symptoms and may include:

- Nasogastric tube feeding

- Gastrostomy

- Oxygen therapy

- Surgical corrections

- Early imaging and examinations for malignancies

References

Vendola, Catherine et al. “Survival of Texas infants born with trisomies 21, 18, and 13.” American journal of medical genetics, Part A vol. 152A,2 (2010): 360-6. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.33156, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ajmg.a.33156.

Baty, B J et al. “Natural history of trisomy 18 and trisomy 13: I. Growth, physical assessment, medical histories, survival, and recurrence risk.” American journal of medical genetics, vol. 49,2 (1994): 175-88. doi:10.1002/ajmg.1320490204.

Van Dyke, D C, and M Allen. “Clinical management considerations in long-term survivors with trisomy 18.” Pediatrics, vol. 85,5 (1990): 753-9.

Carter, P E et al. “Survival in trisomy 18. Life tables for use in genetic counselling and clinical paediatrics.” Clinical genetics, vol. 27,1 (1985): 59-61. doi:10.1111/j.1399-0004.1985.tb00184.x, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1399-0004.1985.tb00184.x?sid=nlm%3Apubmed.

“Trisomy 18: MedlinePlus Genetics.” Medlineplus.gov, 16 Feb. 2021, www.medlineplus.gov/genetics/condition/trisomy-18. Accessed 14 Dec. 2023.

“Trisomy 18 Syndrome - NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders).” NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders), NORD, 2019 www.rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/trisomy-18-syndrome/. Accessed 14 Dec. 2023.

Trisomy 18 Foundation. www.trisomy18.org/ Accessed 29 Dec. 2023.

Morris, Joan K., and George M. Savva. “The Risk of Fetal Loss Following a Prenatal Diagnosis of Trisomy 13 or Trisomy 18.” American journal of medical genetics. Part A, vol. 146A, no. 7, 1 Apr. 2008, pp. 827–832, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18361449/, https://doi.org/10.1002/ajmg.a.32220

“Trisomy 18 - Pediatrics.” MSD Manual Professional Edition, www.msdmanuals.com/professional/pediatrics/chromosome-and-gene-abnormalities/trisomy-18/?autoredirectid=22537. Accessed 29 Dec. 2023.

Rasmussen, Sonja A et al. “Population-based analyses of mortality in trisomy 13 and trisomy 18.” Pediatrics, vol. 111,4 Pt 1 (2003): 777-84, https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.111.4.777 https://publications.aap.org/pediatrics/article-abstract/111/4/777/63087/Population-Based-Analyses-of-Mortality-in-Trisomy?redirectedFrom=fulltext.

Breathnach, Fionnuala M., et al. “First- and Second-Trimester Screening: Detection of Aneuploidies Other than down Syndrome.” Obstetrics and gynecology, vol. 110, no. 3, 1 Sept. 2007, pp. 651–657, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17766613/, https://doi.org/10.1097/01.AOG.0000278570.76392.a6

Mackie, Anne. “Using Cell‐Free Fetal DNA as a Diagnostic and Screening Test: Current Understanding and Uncertainties.” BJOG: an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology, vol. 124, no. 1, 31 May 2016, pp. 47–47, https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.14123.