Gitelman syndrome (GS), also known as familial hypokalemia-hypomagnesemia, is a rare au-tosomal recessive inherited salt-wasting tubulopathy. The disease is characterized by hypoka-lemic metabolic alkalosis, hypomagnesemia, and hypocalcuria, and symptoms can vary from late childhood to adulthood. The cause is a transport defect in the distal convoluted tubule.

Also called

Gitelman syndrome is also known as:

- GS

- Familial hypokalemia-hypomagnesemia

- Hypokalemia-hypomagnesemia, primary renotubular, with hypocalciuria

- Tubular hypomagnesemia-hypokalemia with hypocalcuria

Symptoms

The phenotype of GS patients is extremely heterogeneous in terms of symptom onset of symptoms and the type and severity of biochemical abnormalities and clinical manifestations. Initial symptoms usually appear from late childhood (>6 years) into adulthood, with most patients presenting during adolescence. However, initial diagnoses can also occur within the neonatal period up to seventh decade of life.

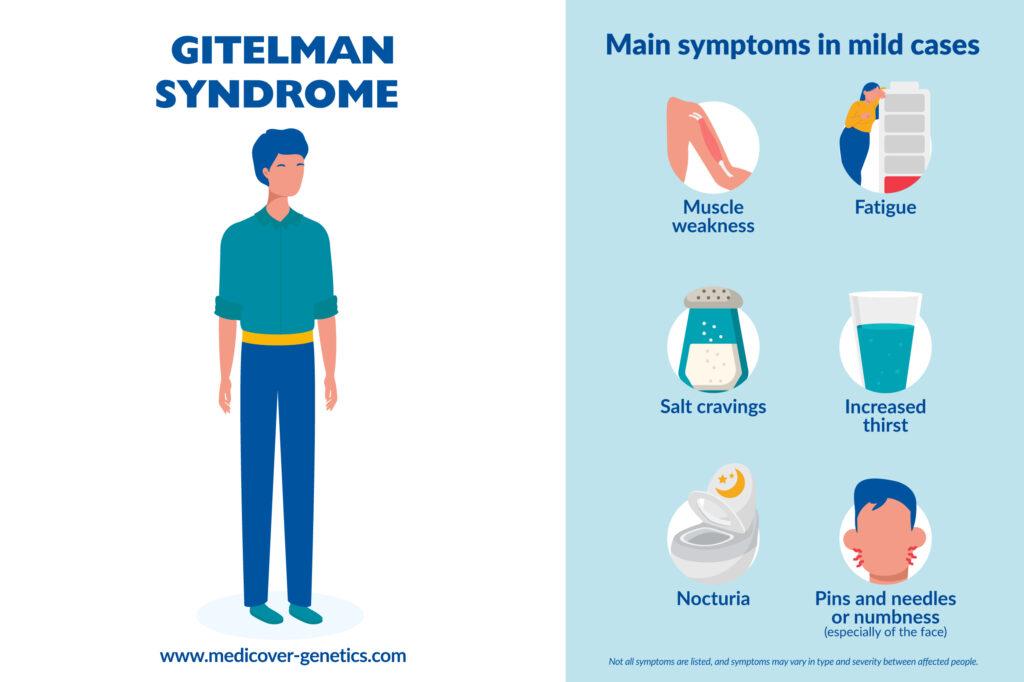

The disease may be asymptomatic or associated with mild symptoms, such as:

- Weakness

- Fatigue

- Salt cravings

- Thirst

- Nocturia

- Transient episodes of muscle weakness and tetany accompanied by abdominal pain, vomiting, and fever

- Paresthesias, especially of the face

Rare severe manifestations may present as early onset of disease under 6 years, such as:

- Growth retardation

- Chondrocalcinosis

- Seizures

- Rhabdomyolysis

Hypokalemia and hypomagnesia prolong the duration of the action potential in cardiomyocytes, increasing the risk of ventricular arrythmias. ECGs of GS patients revealed that in about 50% of cases, the QT interval is mildly to moderately prolonged.

Frequency

The frequency of Gitelman syndrome is estimated to be approximately 1:40,000. However, it is difficult to estimate the actual prevalence, as many cases can go undiagnosed or misdiagnosed.

Causes

In about 80% of adult patients, the cause is loss-of-function variants in the SLC12A3 gene (solute carrier family 12 member 3), which encodes the renal thiazide-sensitive Na-Cl cotransporter (NCC) and is located on the long arm of chromosome 16 (16q13). It is specifically expressed on the apical membrane of cells of the distal convolute. The deficiency of functional NCC leads to metabolic disorders, the consequence being severe electrolyte loss.

Most SLC12A3 variants are missense and nonsense variants; however, frameshift, splice, and deep intronic variants as well as large genomic rearrangements have also been described. Variants are distributed throughout the gene. Genetic heterogeneity is also observed, and a small proportion of patients with the GS phenotype carry pathogenic variants in the CLCNKB gene.

In addition, pathogenic variants in the HNF1B gene, which encodes the transcription factor HNF1-β, can cause GS-typical electrolyte abnormalities (especially hypomagnesemia).

Inheritance

Gitelman syndrome is inherited in an autosomal recessive pattern, meaning that an individual inherits two copies of a mutated gene from their parents who are healthy carriers of the disease.

Differential diagnosis

Syndromes with similar symptoms to Gitelman syndrome include Bartter syndrome and Pseudo-Bartter syndrome.

Treatment

There is no cure for Gitelman syndrome, but treatment is tailored to the individual’s specific symptoms and may include:

- High-salt diet with oral potassium and magnesium supplements diet

- Medication of potassium-sparing diuretics

- Supplementation with magnesium, pain medication and/or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

References

Blanchard, Anne et al. “Gitelman syndrome: consensus and guidance from a Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Controversies Conference.” Kidney international vol. 91,1 (2017): 24-33. doi:10.1016/j.kint.2016.09.046, https://www.kidney-international.org/article/S0085-2538(16)30602-0/fulltext.

Lee, Jae Wook, et al. “Mutations in SLC12A3 and CLCNKB and Their Correlation with Clinical Phenotype in Patients with Gitelman and Gitelman-like Syndrome.” Journal of Korean Medical Science, vol. 31, no. 1, 2016, p. 47, https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2016.31.1.47.

Nakhoul, Farid et al. “Gitelman's syndrome: a pathophysiological and clinical update.” Endocrine vol. 41,1 (2012): 53-7. doi:10.1007/s12020-011-9556-0, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12020-011-9556-0.

Vargas-Poussou, Rosa et al. “Spectrum of mutations in Gitelman syndrome.” Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN vol. 22,4 (2011): 693-703. doi:10.1681/ASN.2010090907, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3065225/.

Balavoine, A S et al. “Phenotype-genotype correlation and follow-up in adult patients with hypokalaemia of renal origin suggesting Gitelman syndrome.” European journal of endocrinology vol. 165,4 (2011): 665-73. doi:10.1530/EJE-11-0224, https://academic.oup.com/ejendo/article-abstract/165/4/665/6676881?redirectedFrom=fulltext&login=false.

“Gitelman Syndrome - Symptoms, Causes, Treatment | NORD.” Rarediseases.org, www.rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/gitelman-syndrome/#disease-overview-main. Accessed 12 Dec. 2023.

Gitelman Syndrome: MedlinePlus Genetics.” Medlineplus.gov, www.medlineplus.gov/genetics/condition/gitelman-syndrome/. Accessed 12 Dec. 2023.